In 1971 Tim Gallwey, founder of the Inner Game, was working as a tennis coach. Having captained the tennis team at Harvard, he was on sabbatical before finding a serious job. One day he noticed that when he left the court briefly, a student who had been stuck with a technical problem had improved, without his help, by the time he returned. He began to realise that people could teach themselves better while working alone than when being given conventional sports instruction by a coach.

Gallwey started to develop a new way of coaching, which focused on enhancing the student’s awareness of what was happening with the ball, the racket and the student’s own body. He developed a series of questions and instructions to achieve this.

Self 1 and Self 2

Tim Gallwey theorised that in every player, and indeed in every one of us, there is a ‘Self 1’ and a ‘Self 2’. Self 1 provides a running commentary on everything that Self 2 does – and it is often a critical one. Self 1 not only reminds Self 2 of the baggage of previous failure, but creates the tension and fear that tend to beset us when we are confronted by a challenge. In fact, Self 1 is creating the worst of the challenges, yet manages to throw all the blame onto Self 2, with inner dialogue like ‘you really blew that; you’ll never be any good at this.’

Performance = potential – interference

Gallwey created the equation “performance = potential – interference” to describe the effect of Self 1’s interference:

This bears a similarity to coaching techniques of identifying limiting beliefs, and Nancy Kline’s questions about limiting assumptions.

Gallwey found a way of getting round Self 1’s interference with instructions like ‘focus on the seams of the ball’, instead of ‘try to hit it in the centre of the racket’. He discovered that directing the student’s attention towards something inconsequential in terms of successful playing was a way of shutting out the nagging voice of Self 1. His pupils’ techniques improved dramatically.

Self 1 and Self 2 in action

I witnessed this principle in action during a demonstration with Tim Gallwey at Queens Club in London. A woman volunteered who told us she had no experience of tennis at all. Gallwey asked her to say ‘bounce’ when the ball bounced and ‘hit’ when it came into contact with the racket of either opponent. The resulting volley lasted for several minutes until he brought it to an end – and she never missed a ball. Because her focus was absorbed in noticing when the ball bounced or hit her racket, the chattering of Self 1 was silenced and her instincts, intuition and unconscious mind were given full play.

This was a visual exercise, and Gallwey has also found that listening to the sound the ball makes, and feeling one’s grip on the racket, are effective in silencing Self 1 and improving focus. This relates to the VAK (Visual, Auditory and Kinaesthetic) preferences defined by psychologists as early as the 1920s.

The opponent within one’s own head

We have all experienced times when we were ‘in the zone’ – for example, a moment when we played the perfect shot, or wrote the right lines, won a deal, or played an instrument. The interference of Self 1’s critical voice is silenced during these times. The techniques which Tim Gallwey developed help people attain that state. He realised that the real obstacles to playing well lie in the player, not in the skill of the opponent and is famously quoted as saying:

Gallwey expounded his theories in the best-selling ‘Inner Game of Tennis’ and went on to write four more books applying the Inner Game to golf, skiing, music and, most notably, ‘The Inner Game of Work’, written after business managers had started to pick up on the techniques and ask how they could be applied in the workplace. His theories were also discovered by Sir John Whitmore, who developed the principles into performance coaching, applied first in sport and later at work.

The Inner Game at work

Tim Gallwey’s first corporate Inner Game assignment was at AT&T, where he was asked to improve courtesy levels in customer service. He agreed to take on the challenge on condition that he did not have to mention the word ‘courtesy’! The customer’s voice became the tennis ball, and operators were asked to identify its tone – whether loud, soft, angry or nervous – and recognise the tones in their own voices. They started to measure the qualities on a scale of 1-10. The process worked on a number of levels, not only improving the relationships between operators and customers, but providing the operators with a more enjoyable workplace, because what they were doing seemed like a game.

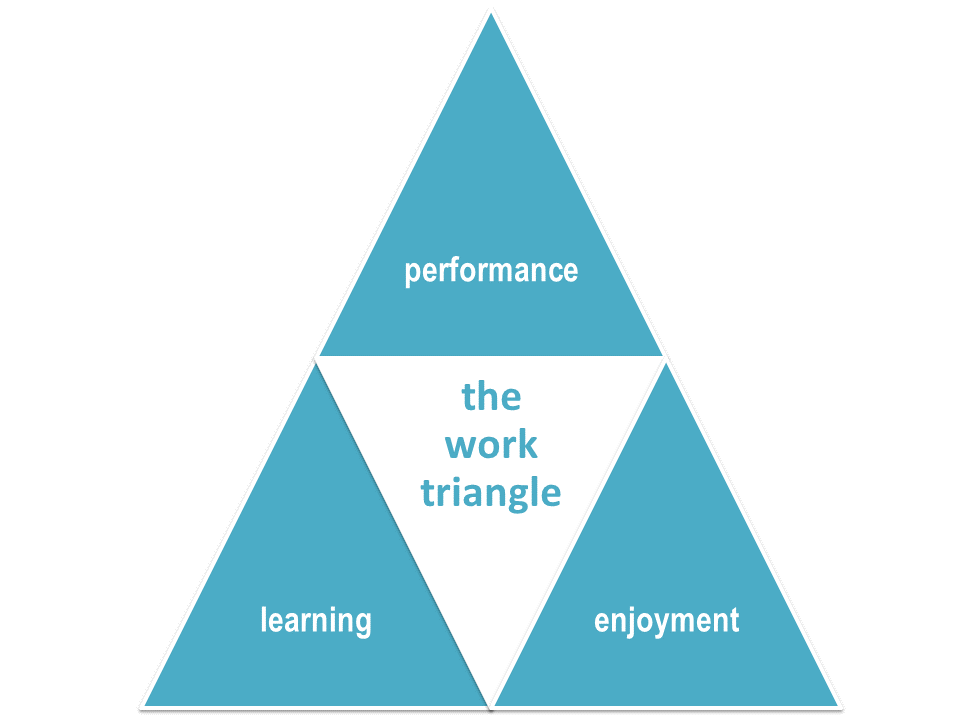

The Work Triangle

One of Tim Gallwey’s illuminating models is ‘The Work Triangle”:

When working under pressure for extended periods, we often dream of giving it all up and spending the rest of our lives lying on a beach. However, when we finally go on holiday and have the chance to do exactly that, within a few days we find ourselves wanting to hire a car, read a book or go for a walk. Gallwey identified that we need a balance of the three elements in everything we do in order for us to feel contented, satisfied and perform at our best.

Critical variables

An essential part of the Inner Game process is to identify what Tim Gallwey termed the ‘critical variables’ – the elements of any situation which matter, as opposed to those that don’t. The critical variables are not always the obvious ones and defining them can produce some valuable insights as well as providing guidance on how to move forward.

Non-judgemental awareness

Another core principle of the Inner Game is non-judgemental awareness – simply asking questions which bring about an awareness of what is happening in any situation, physically, mentally and emotionally. It is reminiscent of the ancient philosophy of Mindfulness, which is also gaining credence in the workplace today. For example, if you find your neck hurts because you have been driving for too many hours, and you pay attention to what needs adjusting, whether position or level of tension, the pain will ease. An emotional application might be when you feel angry or resentful at someone else’s behaviour: just becoming aware of the effects this is having on you enable you to function alongside the feeling without being overwhelmed by it. I have found this particularly useful for clients working in situations where they cannot do much about another person’s behaviour, for example, having a boss who is a bully.

Keeping the focus on the client

Although Tim Gallwey’s work has contributed on a fundamental level to the field of coaching, these days he is concerned that sometimes the coach’s own performance becomes the coach’s focal point, instead of that of the client. He stresses the necessity for the coach to step back and allow people to learn for themselves, whether they be managers, sports players or children. The key is ‘self-directed learning’, which is achieved by keeping the focus on the coachee not the coach:

References:

Gallwey T. Inner Game series

Kline N. Time to Think

Whitmore J. Coaching for Performance

Wilson, C. (2020) Performance Coaching: A Complete Guide to Best Practice Coaching and Training London, Kogan Page.

www.innergame.com

About the author

International speaker, writer and broadcaster Carol Wilson is Managing Director of Culture at Work and a Fellow of the Institute of Leadership & Management, the Professional Speaking Association and the Association for Coaching, where she is a member of the Global Advisory Panel. A cross-cultural expert, she designs and delivers programmes to create coaching cultures for corporate and public sector organisations worldwide and has won awards for coaching and writing. She is the author of ‘Performance Coaching: A Complete Guide to Best Practice Coaching and Training’, now in its third edition and featuring Forewords by Sir Richard Branson and Sir John Whitmore, and ‘The Work and Life of David Grove: Clean Language and Emergent Knowledge’. She has contributed to several other books and published over 60 articles including a monthly column in Training Journal.